Tremolierstich

Tremolierstich

I had been under the impression that the Tremolierstich was used from the Middle Ages to assay purity in German lands, but I'd like to know if it was always present, or if in the case of, say, 12 loths (.750), the Tremolierstich was used? I have a large spoon marked only with 12 (.750), and with some forks marked 13 (.813), which I've always assumed were German, but now ask if there were regions or occasions where the Tremolierstich would not be used? Can someone advise me about the regional limitations of the Tremolierstich? Is there any custom as to where the purity (12 or 13) was placed on cutlery?

Re: Tremolierstich

Hello,

your questions can only be answered in very general terms. Usually German guilds oversaw the punching of hallmarks and control of fineness. It was pretty much up to them when or if the many local rules and regulations were inforced. There is no pattern where control was stricter than in other regions of Germany. A Maker was not under control all the time. Just from time to time the guild would check some of his objects, remove a little silver from 5 to 10 of his pieces (thus causing the "Tremolierstich" on each) and check the fineness. Even if the standard was not met not much happened to the maker. He would possibly be fined a certain sum, but even if he did not pay (which happend more than once) he could go on producing.

So all this was handled in quite a relaxed way. How relaxed did not come out until about 1915/16. During the first years of WW I old silver was collected in Germany to be melted down for the war effort. Art historians together with scientists took the opportunity to check the fineness of many older pieces, scientific methods being much exacter now than before. To their great astonishment they found that the majority of older pieces did not meet the silver standard they should have met. Obviously the old system of control had not worked well.

As to the placing of the marks - traditionally German forks and spoons were punched on the back of the handle, often in the middle, give or take an inch or two. Knife handles and other hollow handles were often punched with the number for the fineness only, sometimes they were not marked at all, though being made of silver. Rarely the end of a handle was marked, this was done only if the shape of the handle allowed.

Regards, Bahner

your questions can only be answered in very general terms. Usually German guilds oversaw the punching of hallmarks and control of fineness. It was pretty much up to them when or if the many local rules and regulations were inforced. There is no pattern where control was stricter than in other regions of Germany. A Maker was not under control all the time. Just from time to time the guild would check some of his objects, remove a little silver from 5 to 10 of his pieces (thus causing the "Tremolierstich" on each) and check the fineness. Even if the standard was not met not much happened to the maker. He would possibly be fined a certain sum, but even if he did not pay (which happend more than once) he could go on producing.

So all this was handled in quite a relaxed way. How relaxed did not come out until about 1915/16. During the first years of WW I old silver was collected in Germany to be melted down for the war effort. Art historians together with scientists took the opportunity to check the fineness of many older pieces, scientific methods being much exacter now than before. To their great astonishment they found that the majority of older pieces did not meet the silver standard they should have met. Obviously the old system of control had not worked well.

As to the placing of the marks - traditionally German forks and spoons were punched on the back of the handle, often in the middle, give or take an inch or two. Knife handles and other hollow handles were often punched with the number for the fineness only, sometimes they were not marked at all, though being made of silver. Rarely the end of a handle was marked, this was done only if the shape of the handle allowed.

Regards, Bahner

Re: Tremolierstich

Bahner`s comment demystifies our perception of ideal silversmithing and assaying in the past.

History cannot be judged from today`s perspective, including assaying silver, not only in Germany but elsewhere, too.

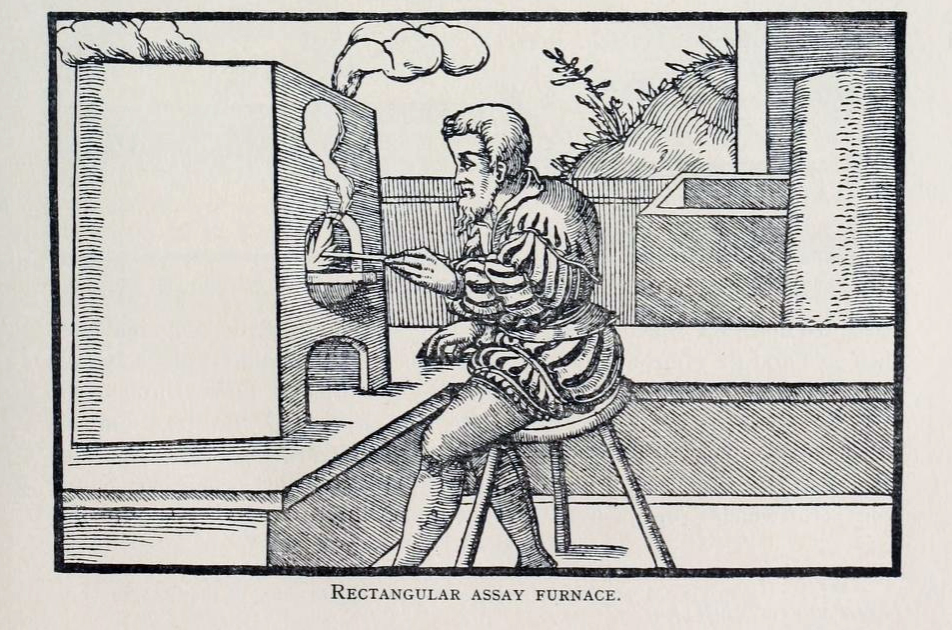

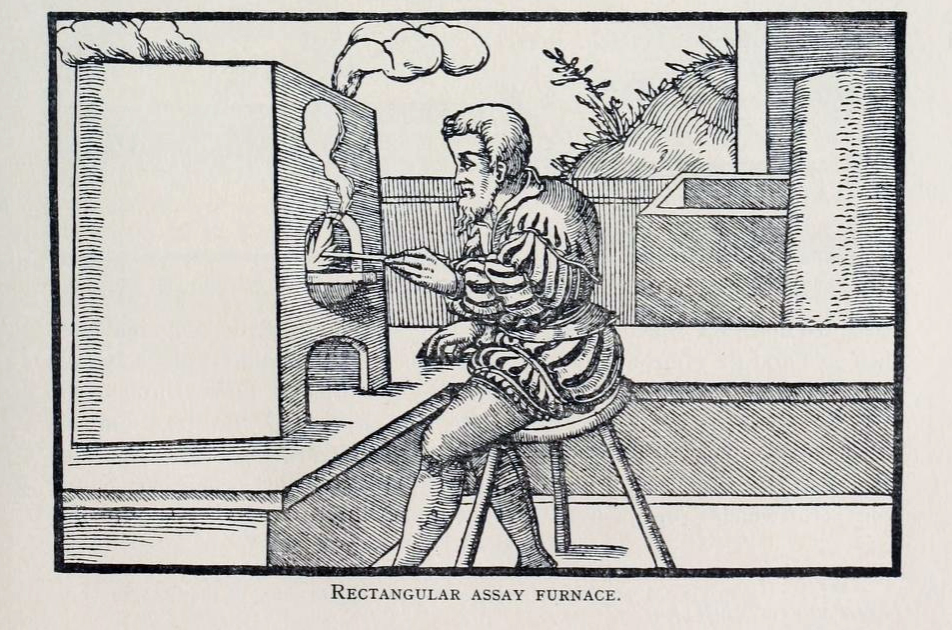

The only method available to assayers at the time was time consuming fire testing.

Cupellation as a purity test

When determining the silver content of an alloy testing process goes as follows. A certain amount of silver is removed from the item. This removed material is weighed and its weight recorded. The material is then cuppeled so that all base metals are removed. Pure silver remains, filtered out and weighed again. Any weight loss represents the amount of added materials and therefore the purity of silver object can be determined.

Imagine this done on every spoon, teapot handle etc. No way.

History cannot be judged from today`s perspective, including assaying silver, not only in Germany but elsewhere, too.

The only method available to assayers at the time was time consuming fire testing.

Cupellation as a purity test

When determining the silver content of an alloy testing process goes as follows. A certain amount of silver is removed from the item. This removed material is weighed and its weight recorded. The material is then cuppeled so that all base metals are removed. Pure silver remains, filtered out and weighed again. Any weight loss represents the amount of added materials and therefore the purity of silver object can be determined.

Imagine this done on every spoon, teapot handle etc. No way.

Re: Tremolierstich

Cupellation is a very old and time consuming method to determine the silver fineness.

Cupellation is a refining process in metallurgy, where ores or alloyed metals are treated under very high temperatures and have controlled operations to separate noble metals, like gold and silver, from base metals like lead, copper, zinc, arsenic, antimony or bismuth, present in the ore.The process is based on the principle that precious metals do not oxidize or react chemically, unlike the base metals; so when they are heated at high temperatures, the precious metals remain apart and the others react forming slags or other compounds

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cupellation

Touch needles, touchstone.

Georgius Agricola (1490–1555) described the use of the touchstone and touch needles for examining bullion, coins, and jewellery.

Dutch silver town guilds assay rules and limitations 17th to 18th century.

The simplest method used for small work was the touch needle and touchstone, with little metal lost. The principle was simple; the touch needle, whose standard of fineness was precisely known, was scratched over a certain kind of black stone (lydite), such that a silver-colored stripe came on the stone. Than the various parts of the silver work to be tested were scratched over the stone, and the assayer's eye determined how the color of the lines diverged from the color of the first line made by the touch needle. More red in color than the touch needle line meant a higher admixture of copper and thus a lower silver fineness. An experienced assayer sees differences in silver content of 5 to 10 thousandths. The color determination was rather subjective and often triggered a quarrel among silversmiths, assayers and guild authorities. Nowadays the touch needle & stone is well-standardized and still the most widely used method.

Tremulierstrich/tremolierstich/zig zag line made by assayer taking a silver sample and to test if the silver sample was of the correct legal standard of fineness. The removed silver sample was compared to another fixed sample of silver with an accurate known legal standard of fineness.

Assaying by tremulierstrich or silver removal, again much depending on the knowledge and experience of the assayer, or the assayer's eye. With a tremble needle the assayer stabbed some silver out of the silver work for assaying. The removed silver sample together with a sample of silver of accurate known fineness was short and lightly annealed (heated) and then quickly cooled down. Comparison of the colors of the two samples, created by the heating, made the determination of the fineness possible. Assaying by tremulierstrich takes far more time compared to the use of touch needle and touchstone and was certainly not more accurate.

However the Guilds/ State/City/Mint authorities decided which assay method had to be applied. If both methods of testing either by touch needle or tremulierstrich were not conclusive or the assayer was in doubt and or the silversmith did not accept the outcome of the assay. The guild authorities ordered assay by Cupellation which could damage the silver work due to multiple silver removal.

During the Dutch silver guild period rules were strict but not all Dutch town guilds strictly obeyed the rules. During the time some guilds received a warning from State/Provincial Authorities for not following the assay rules and or sloppy assay work, even fraud.

Regards,

Peter

Cupellation is a refining process in metallurgy, where ores or alloyed metals are treated under very high temperatures and have controlled operations to separate noble metals, like gold and silver, from base metals like lead, copper, zinc, arsenic, antimony or bismuth, present in the ore.The process is based on the principle that precious metals do not oxidize or react chemically, unlike the base metals; so when they are heated at high temperatures, the precious metals remain apart and the others react forming slags or other compounds

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cupellation

Touch needles, touchstone.

Georgius Agricola (1490–1555) described the use of the touchstone and touch needles for examining bullion, coins, and jewellery.

Dutch silver town guilds assay rules and limitations 17th to 18th century.

The simplest method used for small work was the touch needle and touchstone, with little metal lost. The principle was simple; the touch needle, whose standard of fineness was precisely known, was scratched over a certain kind of black stone (lydite), such that a silver-colored stripe came on the stone. Than the various parts of the silver work to be tested were scratched over the stone, and the assayer's eye determined how the color of the lines diverged from the color of the first line made by the touch needle. More red in color than the touch needle line meant a higher admixture of copper and thus a lower silver fineness. An experienced assayer sees differences in silver content of 5 to 10 thousandths. The color determination was rather subjective and often triggered a quarrel among silversmiths, assayers and guild authorities. Nowadays the touch needle & stone is well-standardized and still the most widely used method.

Tremulierstrich/tremolierstich/zig zag line made by assayer taking a silver sample and to test if the silver sample was of the correct legal standard of fineness. The removed silver sample was compared to another fixed sample of silver with an accurate known legal standard of fineness.

Assaying by tremulierstrich or silver removal, again much depending on the knowledge and experience of the assayer, or the assayer's eye. With a tremble needle the assayer stabbed some silver out of the silver work for assaying. The removed silver sample together with a sample of silver of accurate known fineness was short and lightly annealed (heated) and then quickly cooled down. Comparison of the colors of the two samples, created by the heating, made the determination of the fineness possible. Assaying by tremulierstrich takes far more time compared to the use of touch needle and touchstone and was certainly not more accurate.

However the Guilds/ State/City/Mint authorities decided which assay method had to be applied. If both methods of testing either by touch needle or tremulierstrich were not conclusive or the assayer was in doubt and or the silversmith did not accept the outcome of the assay. The guild authorities ordered assay by Cupellation which could damage the silver work due to multiple silver removal.

During the Dutch silver guild period rules were strict but not all Dutch town guilds strictly obeyed the rules. During the time some guilds received a warning from State/Provincial Authorities for not following the assay rules and or sloppy assay work, even fraud.

Regards,

Peter

Re: Tremolierstich

Very interesting thread, but different sources, different information

On the book by Piero Pazzi "L’oro di Venezia" you read

The "sazo” (assay in Venetian dialect) was used almost exclusively for silver objects whose weight exceeded two ounces. From the object was removed by a zigzag line (ciappolatura in Italian) a small amount of metal that was placed over some burning charcoal so that it could be observed in the fusion phase to establish with a certain reference (that is, another precious metal piece of which the fineness was known) any differences in melting due to the alloy.

The second method, that of touch, was much simpler, it was used for almost all gold and silver items whose weight was less than two ounces. It consisted of scraping with the object to examine a special stone known as the touch stone. On this stripe was then poured a drop of acid and if the stripe did not erase, it was certain that the alloy of the object was not inferior to that for which the acid solution had been arranged.

Instead, on Giovanni Raspini's book

Argenti toscani del '700 e dell'800 e l'Archivio inedito di Costantino Bulgari sugli argenti toscani (Tuscans silverware from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and the unpublished archive of Constantine Bulgari on the Tuscan silverware) reads

They picked up a small amount of metal by a zigzag line, two or three tenths of a gram was enough, placed in a cup, and adding reagents, lead and other, heating and weighing they determined fineness. Another method was the touch; Rubbed (touched) the object on a touch stone and comparing other "rubbing" of known fineness, helping with a few drops of acid, they had the result. But this second method did not involve metal detachment and was less precise.

Maybe in different town there were different costum.

As far as I know the acid method is used for gold, but not for silver.

Regards

Amena

On the book by Piero Pazzi "L’oro di Venezia" you read

The "sazo” (assay in Venetian dialect) was used almost exclusively for silver objects whose weight exceeded two ounces. From the object was removed by a zigzag line (ciappolatura in Italian) a small amount of metal that was placed over some burning charcoal so that it could be observed in the fusion phase to establish with a certain reference (that is, another precious metal piece of which the fineness was known) any differences in melting due to the alloy.

The second method, that of touch, was much simpler, it was used for almost all gold and silver items whose weight was less than two ounces. It consisted of scraping with the object to examine a special stone known as the touch stone. On this stripe was then poured a drop of acid and if the stripe did not erase, it was certain that the alloy of the object was not inferior to that for which the acid solution had been arranged.

Instead, on Giovanni Raspini's book

Argenti toscani del '700 e dell'800 e l'Archivio inedito di Costantino Bulgari sugli argenti toscani (Tuscans silverware from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and the unpublished archive of Constantine Bulgari on the Tuscan silverware) reads

They picked up a small amount of metal by a zigzag line, two or three tenths of a gram was enough, placed in a cup, and adding reagents, lead and other, heating and weighing they determined fineness. Another method was the touch; Rubbed (touched) the object on a touch stone and comparing other "rubbing" of known fineness, helping with a few drops of acid, they had the result. But this second method did not involve metal detachment and was less precise.

Maybe in different town there were different costum.

As far as I know the acid method is used for gold, but not for silver.

Regards

Amena