Online Encyclopedia of Silver Marks, Hallmarks & Makers' Marks

| |||||||

At any rate, his name lives on in the beautiful flatware his firm produced.

The Watts firm retailed as well as manufactured flatware, since some Watts pieces are struck with a "James Watts" incuse mark as well as the more familiar "horsehead over chevron" manufacturing mark. (An anomaly is the ARUM LEAF in Fig.6 marked with both "James Watts" and the retailer mark of "J. Peters & Co." as well as the horsehead.) One would in any case suppose that some sort of brochure or catalogue would be shown to prospective wholesale or retail customers. Yet as far as I know, not one Watts manufacturer's or retailer's catalogue showing the flatware patterns the firm produced has ever turned up.

The second mark in Fig.1 is rarely found and looks as if it has been struck and then engraved, although this is doubtful. The eagle is facing right instead of left, and in some examples there is no curved bar. These two marks seem to have been used simultaneously during the 1850's and early-to-mid-1860's. Finally #3 shows the standard Watts mark, which is found not only on patterns of the 1860's, but also on those which place themselves stylistically in the post-1875 era.

There are variations within in these three main groups as well. As one punch wore out, it would have to be replaced. One has to remember that an early pattern can carry the #3 mark, since we do not know if or when a particular pattern was retired. Questions have been raised about the 4th mark in Fig.1: an arrow facing right, a W, and a shield. Was it another Watts mark, having been found next to his italicized incuse mark? A friend has postulated that the different marks could have been associated with different Watts partnerships. We know that at various times Watts did enter into partnership with other silversmiths or jewelers/watchmakers. However, at least one did have its own manufacturing mark, shown as number 5 in Fig.1: that of Watts & Harper (Henry Harper, partnership working ca. 1859-62). Other partnerships included J. & W. (William) Watts (ca. 1839-52)2, Watts & Butler (James P. Butler, ca. 1867), Watts & Son (James A. Watts, ca. 1881-3 or beyond) and Watts & Moxley or Moseley (Geo. W., 1883; this was Watts' son's partnership).

The #6 mark in Fig.1 is not a Watts mark at all, but that of a fellow Philadelphia silversmithing firm: either that of James P. Butler or of Butler and McCarty. The mark is frequently mistaken for a Watts mark, but the animal's head (eagle?) differs from the Watts eagle in mark #2, and in place of the chevron there is a shield with a 5-pointed star in its center. Although some stampings make the animal head look solidly dark instead of an outline, I believe that there are no variations to this mark. Despite the fact that Watts' firm lasted well into the sterling era, I have never seen a "sterling" mark on his flatware. Did he continue to produce .900 fine silver his entire working career, or did he switch over to the sterling standard and simply not bother with stamping a standard mark? If an inexpensive, non-invasive technique becomes available, it would be interesting to analyze the silver content of later Watts pieces.

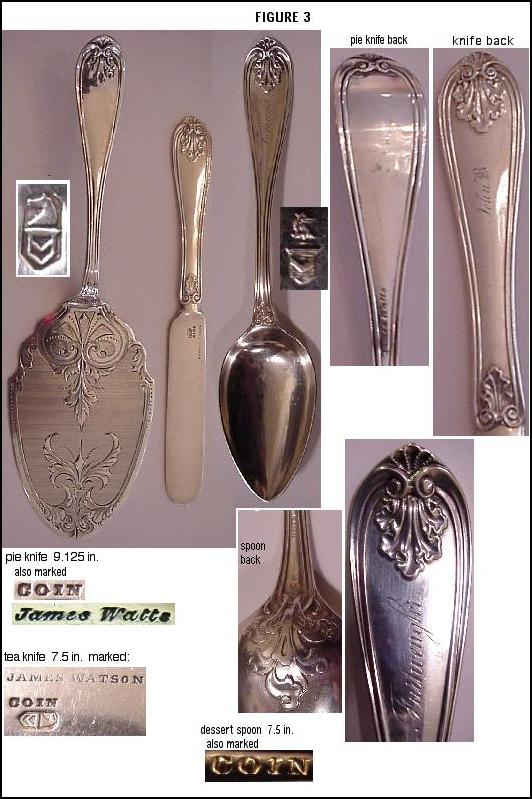

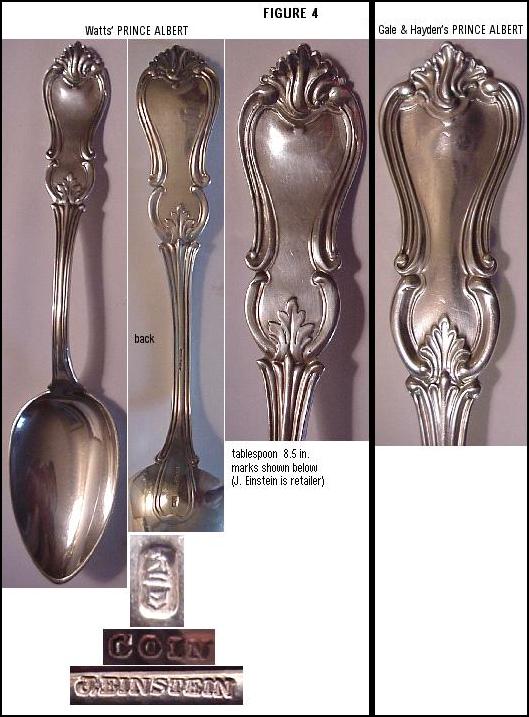

However Watts did make several die-struck patterns, and these are shown in Figs.3 through 8. With the exception of SHELL they are all double dies, with the reverse almost always being a simplified design of the obverse. The pattern shown in Fig.3, similar to Gorham's patented JOSEPHINE, is the most commonly seen, and would date from around the same time as the Gorham patent, 1855. The reverse does not carry the leaf form except on the flat-handled knives. Like many other American coin manufacturers, Watts made the English-originated PRINCE ALBERT pattern (Fig.4). In Watts' variation, the classic KINGS shape of, say, Gale & Hayden (shown in the figure) is modified to a more rounded shape at the top.

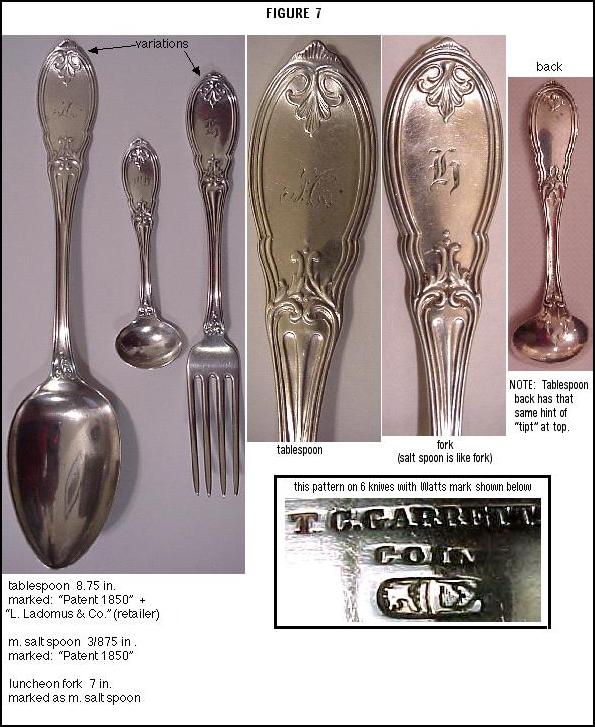

MAYFLOWER (not to be confused with the Baltimore or the William Gale/Theodore Evans designs of the same name) was another pattern which was made by several silversmiths, notably Albert Coles. Watts' version differs slightly in its details. (Fig.5). Both MAYFLFOWER and PRINCE ALBERT were probably introduced in the 1850's. The most common Watts-only pattern is ARUM LEAF (Fig.6), probably introduced in the mid-to-late 1850's. As in JOSEPHINE the reverse omits the large top leaf on spoons and forks. This pattern has also been seen with the mark of Watts & Harper. FANCY LEAF, a rarer pattern (Fig.7), was produced in two variations, but the difference is hardly noticeable. In one variant the thread at the top curves down into the leaf form, whilst in the other (and on both backs) the thread continues unbroken across the top. The reverse's scroll designs differ slightly from the obverse's on spoons and forks. Most of the examples of this pattern are unmarked, but I have seen the #1 Watts mark on 6 flat-handled knives. SHELL (Fig.8) is a combination of a die-struck shell design and roulettework with feather-edging.

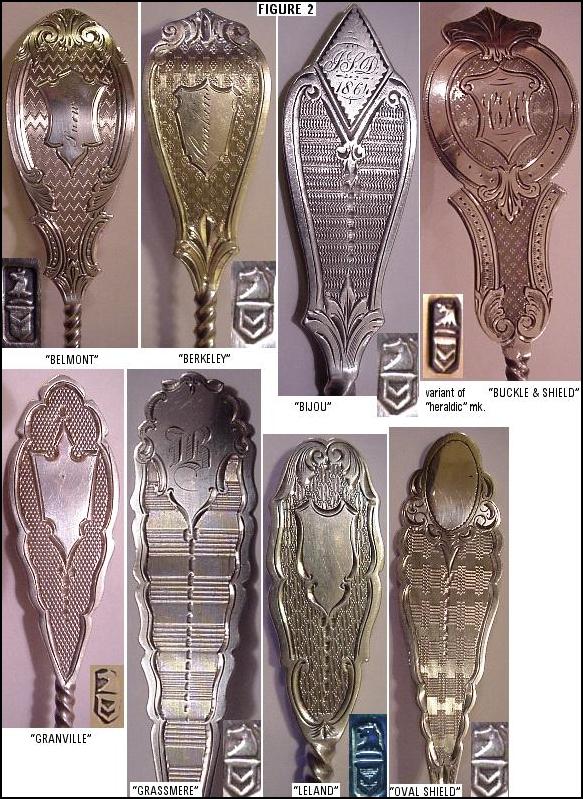

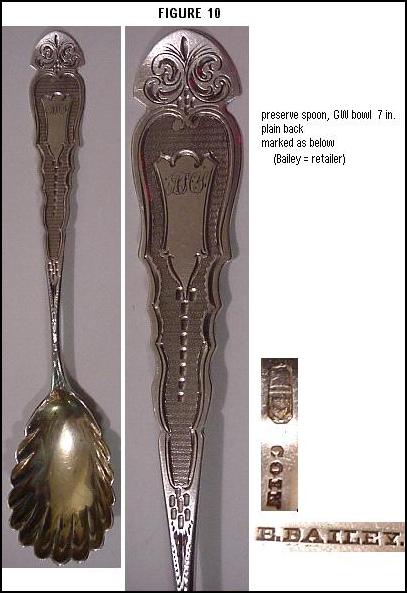

Watts was a manufacturer who liked to utilize interesting shapes for his blanks. More pieces with these fanciful outlines carry the Watts mark than those of other silversmiths of the period, although Joseph Seymour of Syracuse, NY, used them as well. STOWE (Fig.10) is an extreme example of Watts' delight in these outlines.

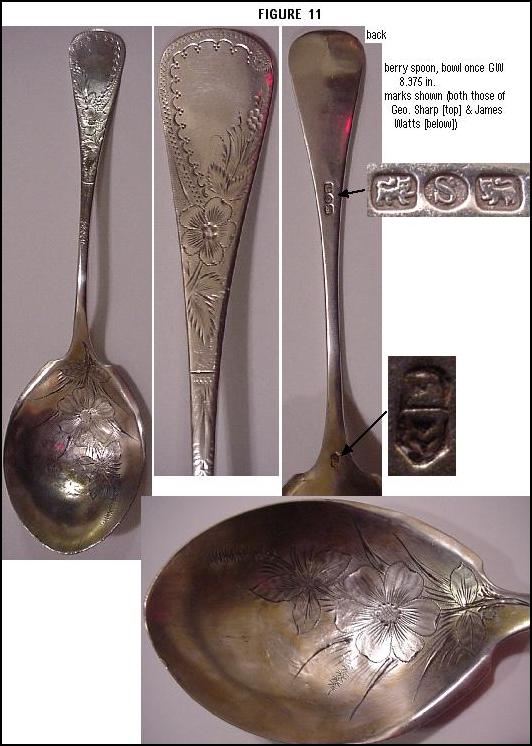

Another example of the possibility of Watts buying up Sharp stock is shown in Fig.12. The pattern is clearly Sharp's blank for his BULL'S HEAD pattern. Watts chose not to attach the bull's head and merely engraved the blank. I remember reading a discussion of a similar case in Silver Magazine--an article by V. Stephen Vaughan in the May-June, 1988, issue1 with additions/corrections by D. Albert Soeffing in the September-October issue5. Dr. Soeffing proposed the buy-up idea at that time.

Only four engraved patterns have come to my notice whose design is characteristic of the mid-1870's or later. These are BIRD ENGRAVED (Fig.13), POINTED END ENGRAVED (CROSSED BANDS), ANTIQUE ENGRAVED (SPRIG) and WARBLER (Fig.14 a, b & c). The first seems to have been Watts' entry in the "battle of the birds," as Dr. Soeffing has termed the 1870's craze to produce patterns incorporating bird designs6. Unlike many of the others, this was not a multi-motif pattern. (Incidentally, Fig.13 shows a piece of this exact pattern marked with the [lion] [S] [lion] of George Sharp, lending credence to Dr. Soeffing's theory of a Watts' buy-up of Sharp stock. Of course, Watts could have bought pieces of this pattern already engraved by Sharp; the engraving is quite similar.) The second resembles Whiting's die-struck pattern NEW HONEYSUCKLE, although different flowers and grasses replace that flower. On both of these pieces, the engraved surface has a satin finish--another signpost that they were made later in Watts' career. The third is a rather generic 1875-85 pattern composed of floral and geometric design elements, as is the forth, with the addition of an engraved bird.

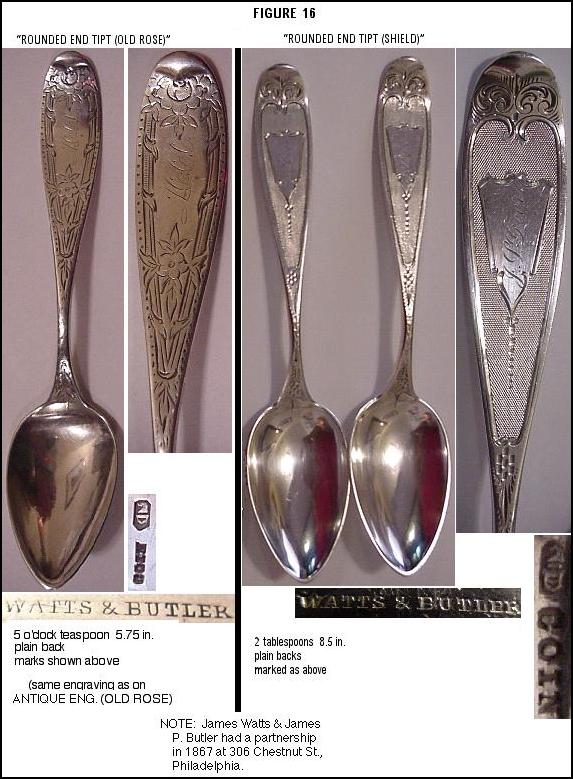

Now we come to patterns marked with backstamps of Watts' partnerships. FEATHER EDGE TIPT (Fig.15a), marked with a "Watts & Butler" backstamp as well as a #3 mark, is a pattern very similar to one made by the Philadelphia maker whose manufacturing mark was "animal head over shield with star" (Fig.15b). As has been mentioned above, I've come to believe that this Philadelphia maker was either the firm of James P. Butler or of Butler & McCarty, since both of those incuse name stamps appear so frequently on "animal head" patterns. The resemblance to the Watts mark suggests a close connection to him, and James P. Butler was in partnership with Watts in 1867. Also, an extensive comparison of Watts and "animal head" pattern designs reveals more than a few similarities. Two variants of a ROUNDED END TIPT, also marked like Fig.15a, are shown in Fig.16.

The Watts & Butler partnership may have been only as a retailer, since a Watts manufacturing mark always appears with the partnership's backstamp. However, the Watts & Harper mark (  ) in my experience never appears with any other manufacturing mark and in fact is seen with other retailer backstamps (Fig.17), leading me to believe that this was a manufacturing partnership. The first of the two examples is very similar in shape to Watts' BERKELEY; I have named it SATHER. A gravy ladle example of the second pattern, called POINTED END TIPT TWIST, exhibits a different iteration of the ) in my experience never appears with any other manufacturing mark and in fact is seen with other retailer backstamps (Fig.17), leading me to believe that this was a manufacturing partnership. The first of the two examples is very similar in shape to Watts' BERKELEY; I have named it SATHER. A gravy ladle example of the second pattern, called POINTED END TIPT TWIST, exhibits a different iteration of the  mark. mark.

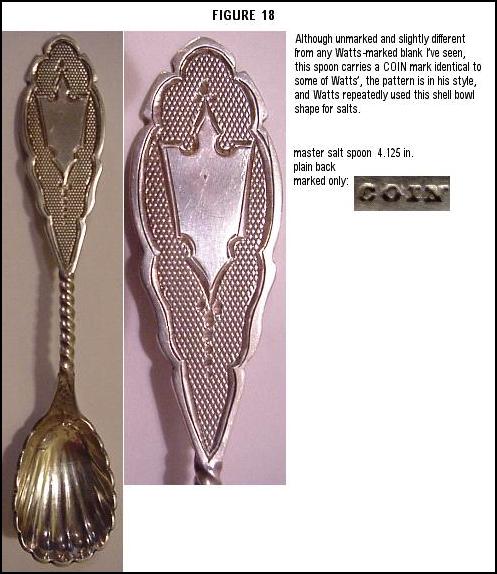

Whilst not identical with other Watts blanks, the unmarked pattern in Fig.18 so resembles GRANVILLE that I have tentatively attributed it to Watts. The danger in doing this is that other Philadelphia silversmiths also made patterns in this style. Peter Krider, Peter Perdriaux, and George Lindner, for example, were fully capable of creating this salt spoon. And George Sharp was another very skilled smith, although fewer engine-turned pieces of his work for Bailey & Co. have come to light than his straight engraved patterns. Sharp's creativity, once he started working under his own mark, took his work in other directions.

I am not an original researcher, and so this article is based only on Watts pieces I have seen and articles I have read about him and his firm. It is hoped that readers will contribute more information and patterns on this prolific nineteenth century manufacturer as they become available. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT: I would like to give credit to V. Stephen Vaughan and D. Albert Soeffing for their original research on Watts. |

|---|

Sources:

1 Vaughan, V. Stephen |

4 Matthews, Martin |