Chinese Export Silver & Far East Trade Information

Re: Chinese Export Silver & Far East Trade Information

SHIBATA

139, West 1st South Street, Salt Lake City

H. S. Shibata, a member of the Japanese jewelry firm at 139 W. 1st South St.. this city, was robbed of $20,000 worth of jewelry by two masked bandits recently while traveling by road 15 miles south of Sacramento, Cal., according to word received here by his brother, R. M. Shibata. Shibata was calling upon the Japanese jewelry retailers on the Pacific Coast, his brother said. The man is not believed to have been seriously hurt by the thugs though it is said he was not able to make a report to the Sacramento police immediately following the robbery.

Source: The Jewelers' Circular - 2nd August 1922

Trev.

139, West 1st South Street, Salt Lake City

H. S. Shibata, a member of the Japanese jewelry firm at 139 W. 1st South St.. this city, was robbed of $20,000 worth of jewelry by two masked bandits recently while traveling by road 15 miles south of Sacramento, Cal., according to word received here by his brother, R. M. Shibata. Shibata was calling upon the Japanese jewelry retailers on the Pacific Coast, his brother said. The man is not believed to have been seriously hurt by the thugs though it is said he was not able to make a report to the Sacramento police immediately following the robbery.

Source: The Jewelers' Circular - 2nd August 1922

Trev.

Re: Chinese Export Silver & Far East Trade Information

The Watch Trade in China

Translated from the Recently Published Report of Dr. Paul Ritter, Swiss Consul at Yokohama

THE duty on watches in China is 5 per cent ad valorem. In general, they enter at Shanghai or Tientsin, whence they are distributed through the interior by native tradesmen, who supply themselves at these ports. The European importer ordinarily delivers to them a paper called "a pass." This is received at the custom house, and states that the merchandise has paid the charges at the port of entry, and is not subject to further duty.

The interior custom houses are a hindrance to the healthy development of trade. The provincial officials act arbitrarily with reference to imports, and seem to have for a tariff only the degrees of the rapacity of the mandarins in charge. In this way the duties collected at the port of entry are made to represent a simple payment on account.

In China all business is conducted through a native intermediary, who is over the persons dealt with and is responsible for their conduct. He acts as interpreter and agent of the European merchant, and affords much protection. Besides his salary, he receives a commission, and it is an open secret that over that he makes as much profit for himself as for the house that employs him. Well informed persons claim that he often makes twice as much as his employers.

Until recent years sales of watches were for cash. Now buyers demand 30 days' and even two months' credit. This postponement of collection is attended with danger, for most of the customers have but a small shop and no capital. So, when the day of payment arrives, the store may be closed and the individual out of sight. From Shanghai to Ningpo, or some other city, is only a few hours by boat, and very alert will be he who can catch the fugitive in these populous centers.

The kinds of watches most in vogue arc those of cheap metal, remontoir lepine. cylinder escapement, of 16 to 18 lines, and silver double case key watches, lever escapement, with engine turned cases. Stemwinders have yet scarcely entered into Chinese commerce.

The timepieces known in Switzerland as "Chinese" have lost much of their old success, owing to the competition of certain houses among themselves. Some marks of established reputation maintain former prices. The introduction of new marks in China is extremely difficult, for the people are more conservative in their ideas and tastes than elsewhere. Nevertheless, new styles have succeeded in overcoming difficulties, and to-day the small gold double case watch of 14 karats registered is sold, as well as some articles for fancy, as eight-day watches, those giving the day of the month and silver double case chronograph repeaters.

The watches imported are mostly of Swiss production. The watch trade has been for a long time mainly in the hands of Swiss houses established at the open ports. For some years, however, they have met with strong competition from German houses at the same ports, who, as commission merchants, have added watches to their trade, and are content with a small profit. Then, the United States become more and more every day a rival with which we have to deal. Their production is excellent. So they have conquered their place in this market, as well as in England and other European countries The marks "Waterbury" and "Waltham" are well known, and often Swiss merchants receive orders for them. Their good qualities assure success and justify hopes of still better results, notwithstanding their prices are a little higher than ours. No fault can be found with their construction.

The general state of trade here, as elsewhere, leaves much to be desired, and competition is much stronger than generally supposed in Switzerland. The scarcity of silver, its constant fluctuation in value as compared with gold, the political condition of this crumbling Empire are so many obstacles against which European merchants have to contend.

In spite of my efforts, it has been impossible to obtain other statistics than those of Shanghai, according to which there were entered at that port in 1897, 32,571 watches, representing a value of 127,651 taels.

Source: The Jewelers' Circular and Horological Review - 27th September 1899

Trev.

Translated from the Recently Published Report of Dr. Paul Ritter, Swiss Consul at Yokohama

THE duty on watches in China is 5 per cent ad valorem. In general, they enter at Shanghai or Tientsin, whence they are distributed through the interior by native tradesmen, who supply themselves at these ports. The European importer ordinarily delivers to them a paper called "a pass." This is received at the custom house, and states that the merchandise has paid the charges at the port of entry, and is not subject to further duty.

The interior custom houses are a hindrance to the healthy development of trade. The provincial officials act arbitrarily with reference to imports, and seem to have for a tariff only the degrees of the rapacity of the mandarins in charge. In this way the duties collected at the port of entry are made to represent a simple payment on account.

In China all business is conducted through a native intermediary, who is over the persons dealt with and is responsible for their conduct. He acts as interpreter and agent of the European merchant, and affords much protection. Besides his salary, he receives a commission, and it is an open secret that over that he makes as much profit for himself as for the house that employs him. Well informed persons claim that he often makes twice as much as his employers.

Until recent years sales of watches were for cash. Now buyers demand 30 days' and even two months' credit. This postponement of collection is attended with danger, for most of the customers have but a small shop and no capital. So, when the day of payment arrives, the store may be closed and the individual out of sight. From Shanghai to Ningpo, or some other city, is only a few hours by boat, and very alert will be he who can catch the fugitive in these populous centers.

The kinds of watches most in vogue arc those of cheap metal, remontoir lepine. cylinder escapement, of 16 to 18 lines, and silver double case key watches, lever escapement, with engine turned cases. Stemwinders have yet scarcely entered into Chinese commerce.

The timepieces known in Switzerland as "Chinese" have lost much of their old success, owing to the competition of certain houses among themselves. Some marks of established reputation maintain former prices. The introduction of new marks in China is extremely difficult, for the people are more conservative in their ideas and tastes than elsewhere. Nevertheless, new styles have succeeded in overcoming difficulties, and to-day the small gold double case watch of 14 karats registered is sold, as well as some articles for fancy, as eight-day watches, those giving the day of the month and silver double case chronograph repeaters.

The watches imported are mostly of Swiss production. The watch trade has been for a long time mainly in the hands of Swiss houses established at the open ports. For some years, however, they have met with strong competition from German houses at the same ports, who, as commission merchants, have added watches to their trade, and are content with a small profit. Then, the United States become more and more every day a rival with which we have to deal. Their production is excellent. So they have conquered their place in this market, as well as in England and other European countries The marks "Waterbury" and "Waltham" are well known, and often Swiss merchants receive orders for them. Their good qualities assure success and justify hopes of still better results, notwithstanding their prices are a little higher than ours. No fault can be found with their construction.

The general state of trade here, as elsewhere, leaves much to be desired, and competition is much stronger than generally supposed in Switzerland. The scarcity of silver, its constant fluctuation in value as compared with gold, the political condition of this crumbling Empire are so many obstacles against which European merchants have to contend.

In spite of my efforts, it has been impossible to obtain other statistics than those of Shanghai, according to which there were entered at that port in 1897, 32,571 watches, representing a value of 127,651 taels.

Source: The Jewelers' Circular and Horological Review - 27th September 1899

Trev.

Re: Chinese Export Silver & Far East Trade Information

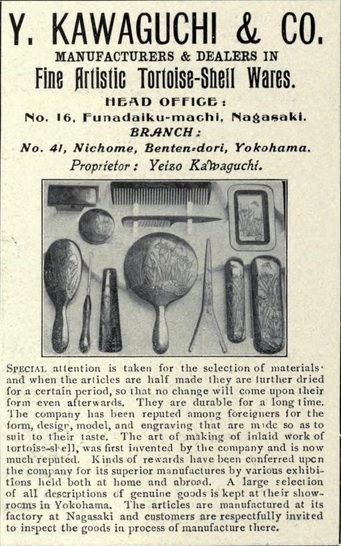

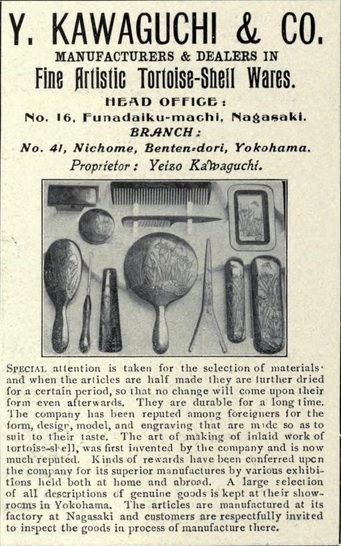

Y. KAWAGUCHI & Co.

16, Funadaiku-machi, Nagasaki, and, 41, Nichome, Benten-dori, Yokohama

Y. Kawaguchi & Co. - Nagasaki and Yokohama - 1910

The business of Yeizo Kawaguchi.

Link to an image of the Kawaguchi store: http://www.mfa.org/collections/object/t ... -co-416806

Trev.

16, Funadaiku-machi, Nagasaki, and, 41, Nichome, Benten-dori, Yokohama

Y. Kawaguchi & Co. - Nagasaki and Yokohama - 1910

The business of Yeizo Kawaguchi.

Link to an image of the Kawaguchi store: http://www.mfa.org/collections/object/t ... -co-416806

Trev.

Re: Chinese Export Silver & Far East Trade Information

Demand for Jewelry and Silverware in Siam

Washington, D. C, June 11.–Judging from the activity at the numerous gold and silversmith shops in Bangkok, writes Vice Consul Carl C. Hansen, Siam, to the Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce, it would appear that there is considerable demand for local made jewelry and silverware, such as chains, necklaces, belts, earrings, finger rings, and bracelets.

Tea sets in repousse patterns, gold and silver vessels, and vases for domestic, temple, and ceremonial use are also products of the Bangkok silversmiths.

Imported jewelry and silverware of western nations is in fair demand, but pre-war prices have not yet been reached, due to the present unfavorable trade conditions. When this situation improves a revival of the foreign jewelry trade is sure to follow.

Approaching social activities at court are also likely to augment the demand for artistic jewelry and gold and silver ware of occidental styles.

The imports of jewelry and all kinds of gold and silversmiths' wares, including plated ware, amounted to 347,971 ticals ($129,062) in 1919-20, against 707,611 ticals ($262,452) in 1913-14. Imports of precious rough stones amounting to 359,296 ticals.

Source: The Jewelers' Circular - 22nd June 1921

Trev.

Washington, D. C, June 11.–Judging from the activity at the numerous gold and silversmith shops in Bangkok, writes Vice Consul Carl C. Hansen, Siam, to the Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce, it would appear that there is considerable demand for local made jewelry and silverware, such as chains, necklaces, belts, earrings, finger rings, and bracelets.

Tea sets in repousse patterns, gold and silver vessels, and vases for domestic, temple, and ceremonial use are also products of the Bangkok silversmiths.

Imported jewelry and silverware of western nations is in fair demand, but pre-war prices have not yet been reached, due to the present unfavorable trade conditions. When this situation improves a revival of the foreign jewelry trade is sure to follow.

Approaching social activities at court are also likely to augment the demand for artistic jewelry and gold and silver ware of occidental styles.

The imports of jewelry and all kinds of gold and silversmiths' wares, including plated ware, amounted to 347,971 ticals ($129,062) in 1919-20, against 707,611 ticals ($262,452) in 1913-14. Imports of precious rough stones amounting to 359,296 ticals.

Source: The Jewelers' Circular - 22nd June 1921

Trev.

Re: Chinese Export Silver & Far East Trade Information

WORLD'S COLUMBIAN EXPOSITION

Chicago

Japan's Interesting Exhibit

M. Kuru, Imperial Commissioner and Director of Works for Japan to the World''s Columbian Exposition, who is at the Victoria Hotel, New York, says that Japan has appropriated $600,000 for an exhibit at the Fair, and that it will be one of the most interesting exhibits at Chicago.

Most of the exhibits, which consist of tea, silks, carved work, gold medals, fans, fancy articles and decorations, have already arrived in Chicago, and will soon be placed in their proper places.

Source: The Jewelers' Circular and Horological Review - 22nd February 1893

Trev.

Chicago

Japan's Interesting Exhibit

M. Kuru, Imperial Commissioner and Director of Works for Japan to the World''s Columbian Exposition, who is at the Victoria Hotel, New York, says that Japan has appropriated $600,000 for an exhibit at the Fair, and that it will be one of the most interesting exhibits at Chicago.

Most of the exhibits, which consist of tea, silks, carved work, gold medals, fans, fancy articles and decorations, have already arrived in Chicago, and will soon be placed in their proper places.

Source: The Jewelers' Circular and Horological Review - 22nd February 1893

Trev.

Re: Chinese Export Silver & Far East Trade Information

Damaskeening in Japan

By Flora Oakley Janes

The swords of Damascus and the minute decoration of their hilts in gold and silver tracery have given a name to a distinct and most interesting form of art work in metal. But as we call porcelain "china" though it may have been made in New Jersey, and never once think of Calcutta when buying or wearing calico, so for the finest damaskeen work in the world at the present time we go not to Syria but to Japan.

Kyoto, the old capital, which for eleven hundred years was the heart and center of every art impulse in the empire, was the seat of the industry in the riper days of the feudal regime. For three hundred years the art has flourished' there in the patronage of court and warring clans; and to-day the most elaborate gold inlaying in Japan is done by a dozen or so of workmen in three little shops in out-of-the-way corners of Kyoto.

In a time when a boy of samurai rank was invested with a sword at the tender age of five; when every gentleman carried two swords as a badge of his position as gentleman and warrior : when war was a genteel trade and the sword the universal weapon: when fashion gruesomely included a dagger among the wedding presents of a bride, and dictated a special dirk for the correct performance of harakiri, it is readily seen why it was that the new craze for art decoration which came into Japan on the wave of Buddhist innovation should have turned to the ornamentation of every part of the sword suitable for ornamentation–the hilt, the guard and the scabbard.

If there is any one thing, however, which more than another stand's for action without any foolery, it is the modern gun-barrel. And so, with the passing of the feudal age, the artist or artisan in sword-hilts was left without a definite occupation. But in late years a steadily growing demand has sprung up in the track of the professional buyer as well as of the foreign tourist. The articles called for are varied enough; but from the Japanese point of view they are singularly alike in that they are all utterly inexplicable and unaccountable, ranging as they do in size and expense from a box for a millionaire to keep his postage stamps in up to an eighteen inch plate–emphatically not for him to put his food on, but to hang on the wall.

Damaskeening, as done in Kyoto, takes one step beyond the possibilities of bronze work, inasmuch as it adds the hair line to the bronzist's methods. All metals and all alloys are laid under contribution, though gold and silver upon iron are given the preference for the fine contrast they afford: while the stress is put

upon inlaying and carving processes rather than upon the fusing and mixing of metals in delicate proportions as in bronze work. One peculiarity is highly

noticeable in all metal work in Japan. A Japanese has no prejudice which lead's him to place one metal before another for its mere costliness, any more than a western artist in oils would think of using his most expensive colors all the time instead of the most effective ones. This may be depended upon as a main distinction between east and west in metal work. Copper, for instance, may very readily take precedence over gold, or iron over either one. The place in the color scale would determine the selection of any particular metal, not its intrinsic value.

All processes possible in combination are at the disposal of the worker in damaskeen. He may inlay, carve, engrave, and even fuse, though he places less reliance upon fusing than the bronzist does. The favorite style of decoration is a medallion inlaid boldly with a scene and set in a ground of workmanship so minute and so eveny distributed that a second look is necessary to resolve what appears to be a sheen into an almost microscopic labyrinth of scrollery and fret.

As is the case with all fine Oriental work, it is impossible to appreciate the beauty of damaskeen without at least so much of knowledge of the exquisite skill and almost superhuman patience spent upon it as may be gained from an hour's visit at a workshop.

First the plate of metal–iron or soft steel–to be ornamented is firmly embedded in a block of rosin to give facility for handling. But iron or soft steel in its crude state is intractable for inlaying. Just as the artist in pastels has to prepare his paper carefully to insure the ready blending of the tints of his picture, the worker in damaskeen must thoroughly and uniformly break up the stubborn texture of his metal plate to obtain a surface which will both receive and hold the inlaid decoration. This work, however important, is but preliminary and is intrusted to the apprentice. So with a toy chisel and a make-believe hammer he sets at work. Moving the chisel slowly over a bit of space as long as the width of the tool, say a quarter of an inch, he beats a continuous tattoo upon its flattened top, the result being a tiny square of vertical hair lines like the shade in an engraving. Then he turns his block at right angles and makes a second

square adjoining the first, turns again and makes a third until the plate has become a checker-board, the squares of which are of alternate vertical and horizontal parallels. This, of course, has taken time, but the work is only just laid out. Again the surface is patiently gone over in the opposite direction–

that is, the vertical hair lines are crossed by horizontal ones and vice versa. A third time the process is repeated with diagonals, and a fourth with other diagonals crossing the previous ones in checks. The master of the shop now runs his finger over the plate and pronounces it ready for the design.

Meantime, the gold has been preparing. This comes from the gold-beater in thin ribbon plates. The master himself cuts them into convenient lengths of about three inches, and then with a pair of scissors which he stops every other minute to whet, he pares one hair's breadth after another so fine that a dozen have to be cut before the ribbon is perceptibly narrowed. A glance over the rim of his goggles now brings a boy to the 'hibachi', who quickly starts a glow among the three or four bits of charcoal by blowing the flame through a bamboo stick with the bellows given him by nature.

It is this extreme simplicity of method and' paucity of means to do with that makes a piece of fine Japanese work of any kind seem little short of a miracle to a "foreign barbarian." It compels an intimacy with raw materials and a sharpening of the faculties that amount in practice to an added sense. A few minutes of blowing and the strips are all cut, the coals bright red and all in readiness. Taking the bamboo tube from the boy and with the other hand deftly picking up a little platinum dish of the gold shavings with a pair of chop-stick tongs, the operator balances the dish nicely on the coals. Before a degree of heat has been reached sufficient to melt the gold, he carefully picks out one of the hot wires, and laying it on a steel plate he rolls it with a spatula until the angles and kinks have disappeared and the wire itself is as fine and even as a hair from a baby's head and almost as pliable. All are treated in turn, and the materials are now ready for manipulation.

A favorite Japanese treatment of damaskeen, as has been said, is a medallion outlined boldly with a coarse wire, within which a design is delicately wrought in gold, it may be in the space of a square inch, to represent, say, a temple garden or a palace park–both subjects commending themselves for minuteness of detail in foliage, water, boats, lanterns, temple roofs, distant mountains, and clouds with an inevitable flight of birds disappearing into them. The ground is then completely filled with some all-over pattern of chrysanthemums or Paulownia, for instance, executed with almost microscopical delicacy and precision.

The article to be decorated may be a fan-shaped jewel box. A medallion of the same shape will be outlined on the lid in coarse silver wire and filled in to represent a vista of hills with water and pine-tree foliage in the background, while the body of the box may be covered with a running pattern of tufts of pine needles. A Greek key may finish the edge of the lid, and the bottom may be covered with an all-over adaptation of the Greek key–a pattern which the Japanese, however, claim as an independent invention of their own, suggested by the lightning. The two steps already described are quite mechanical,

but to produce a pattern or design requires not only a delicate touch and a knowledge of metals amounting almost to an instinct but the ability at least to copy with the utmost accuracy, if not to work a design out and out in free hand. The cross-hatched surface of iron is such as to make a preliminary outline drawing impracticable. The artisan is an artist to the extent that his eye alone must guide and determine his work. When he has mastered his means of expression, his task is the artist's task to make a sketch. lie makes it on an iron plate in lieu of paper with gold wire tracery in place of ink.

Picking up a wire, he touches it to the iron, guides it along with the chisel to form the line he has in mind–a mountain slope, the sag of a cottage thatch, or the pinion of a bird–cuts it oft at the proper length by a slight pressure of the chisel edge and gives the line a few taps with a spidery hammer, repeating the process till the main features of the design are indicated.

The entire plate is then given a thin coat of lacquer, through which, when dried, the gold work is easily made to appear on being rubbed with a steel polisher. The plate is thus made ready for the next less important details. These are then added and lacquer is again applied. The process may be repeated' until a design has been worked over twenty times. By such a mode of procedure, the workman is not only enabled to keep the proper proportions of space which the infinitude of details might otherwise encroach upon, In it lacquer has been so forced into the pores of the iron as to make it proof against rust,

though lacquer does not at all appear on the finished surface. When the last trace of gold has been inlaid, the piece of work, if a receptacle, as a box, vase, or shrine, rather than a flat surface, as a panel or plaque, is lined with gold by hammering a sheet of the pure metal directly upon the interior surface. The whole is then carefully burnished and the work is complete.

Considered as workmanship, damaskeen has great durability. When one end of a wire has been touched to the iron and given a smart tap or two with the hammer, it is possible to draw a heavy plate freely about on the table by the wire or even to lift it in the air. The wire will break before the end will be detached.

To the general field of decorative art, damaskeen holds a relation somewhat similar to that of the sonnet to poetry. The problem is unlimited embellishment of the "scanty plot of ground" enclosed within the rigid limitations of material and space: and to the solution of this problem anything at all in the works of nature or the arts and imaginations of man may be called upon to contribute a design. As may be expected, the national fancy for a grotesque effect finds expression in damaskeen as in everything else the Japanese artist touches ; but the naturally fine taste of this truly aesthetic people always prevents the perpetration of an offence of any kind.

To illustrate the range of ingenuity shown in the selection of a design, I recall a little tray with a cottage and overhanging plum tree in full bloom in the medallion – a theme as common as it is pretty. The medallion was set in the usual net of filagree work, but in the cramped space of each of the interstices was displayed some implement or utensil of the kitchen or general household economy, as if the cottage had been ransacked to provide the scheme for its own setting. A delicately outlined teapot, a gridiron, a dustpan, a shovel and tongs, and forty other homely things all came to light on a close inspection

of the work.

The most ambitious piece of damaskeen I have ever examined was a large iron plaque, representing a theme in which religion, mythology and drollery were combined in about equal proportions. The tracery in this case poetically stood for the unsubstantial veil that is felt to be between this material world and the realm of spirits. Behind it and striving to break through its meshes were horrid monsters of the darkness, which the iron was cleverly used to typify–dragons or hobgoblins with claws, horns, scales, fins and snouts–madIy careering about a temple window, from which a couple of tonsured Buddhist priests were driving them with bell and rosary back to their own proper domain.

Damaskeen may not be an art, and the patience, skill, and' taste required to damaskeen may not amount to genius; but in that case the old definition is at fault which makes genius an "infinite capacity for taking pains."

Source: The Trader and Canadian Jeweller - August 1920

Trev.

By Flora Oakley Janes

The swords of Damascus and the minute decoration of their hilts in gold and silver tracery have given a name to a distinct and most interesting form of art work in metal. But as we call porcelain "china" though it may have been made in New Jersey, and never once think of Calcutta when buying or wearing calico, so for the finest damaskeen work in the world at the present time we go not to Syria but to Japan.

Kyoto, the old capital, which for eleven hundred years was the heart and center of every art impulse in the empire, was the seat of the industry in the riper days of the feudal regime. For three hundred years the art has flourished' there in the patronage of court and warring clans; and to-day the most elaborate gold inlaying in Japan is done by a dozen or so of workmen in three little shops in out-of-the-way corners of Kyoto.

In a time when a boy of samurai rank was invested with a sword at the tender age of five; when every gentleman carried two swords as a badge of his position as gentleman and warrior : when war was a genteel trade and the sword the universal weapon: when fashion gruesomely included a dagger among the wedding presents of a bride, and dictated a special dirk for the correct performance of harakiri, it is readily seen why it was that the new craze for art decoration which came into Japan on the wave of Buddhist innovation should have turned to the ornamentation of every part of the sword suitable for ornamentation–the hilt, the guard and the scabbard.

If there is any one thing, however, which more than another stand's for action without any foolery, it is the modern gun-barrel. And so, with the passing of the feudal age, the artist or artisan in sword-hilts was left without a definite occupation. But in late years a steadily growing demand has sprung up in the track of the professional buyer as well as of the foreign tourist. The articles called for are varied enough; but from the Japanese point of view they are singularly alike in that they are all utterly inexplicable and unaccountable, ranging as they do in size and expense from a box for a millionaire to keep his postage stamps in up to an eighteen inch plate–emphatically not for him to put his food on, but to hang on the wall.

Damaskeening, as done in Kyoto, takes one step beyond the possibilities of bronze work, inasmuch as it adds the hair line to the bronzist's methods. All metals and all alloys are laid under contribution, though gold and silver upon iron are given the preference for the fine contrast they afford: while the stress is put

upon inlaying and carving processes rather than upon the fusing and mixing of metals in delicate proportions as in bronze work. One peculiarity is highly

noticeable in all metal work in Japan. A Japanese has no prejudice which lead's him to place one metal before another for its mere costliness, any more than a western artist in oils would think of using his most expensive colors all the time instead of the most effective ones. This may be depended upon as a main distinction between east and west in metal work. Copper, for instance, may very readily take precedence over gold, or iron over either one. The place in the color scale would determine the selection of any particular metal, not its intrinsic value.

All processes possible in combination are at the disposal of the worker in damaskeen. He may inlay, carve, engrave, and even fuse, though he places less reliance upon fusing than the bronzist does. The favorite style of decoration is a medallion inlaid boldly with a scene and set in a ground of workmanship so minute and so eveny distributed that a second look is necessary to resolve what appears to be a sheen into an almost microscopic labyrinth of scrollery and fret.

As is the case with all fine Oriental work, it is impossible to appreciate the beauty of damaskeen without at least so much of knowledge of the exquisite skill and almost superhuman patience spent upon it as may be gained from an hour's visit at a workshop.

First the plate of metal–iron or soft steel–to be ornamented is firmly embedded in a block of rosin to give facility for handling. But iron or soft steel in its crude state is intractable for inlaying. Just as the artist in pastels has to prepare his paper carefully to insure the ready blending of the tints of his picture, the worker in damaskeen must thoroughly and uniformly break up the stubborn texture of his metal plate to obtain a surface which will both receive and hold the inlaid decoration. This work, however important, is but preliminary and is intrusted to the apprentice. So with a toy chisel and a make-believe hammer he sets at work. Moving the chisel slowly over a bit of space as long as the width of the tool, say a quarter of an inch, he beats a continuous tattoo upon its flattened top, the result being a tiny square of vertical hair lines like the shade in an engraving. Then he turns his block at right angles and makes a second

square adjoining the first, turns again and makes a third until the plate has become a checker-board, the squares of which are of alternate vertical and horizontal parallels. This, of course, has taken time, but the work is only just laid out. Again the surface is patiently gone over in the opposite direction–

that is, the vertical hair lines are crossed by horizontal ones and vice versa. A third time the process is repeated with diagonals, and a fourth with other diagonals crossing the previous ones in checks. The master of the shop now runs his finger over the plate and pronounces it ready for the design.

Meantime, the gold has been preparing. This comes from the gold-beater in thin ribbon plates. The master himself cuts them into convenient lengths of about three inches, and then with a pair of scissors which he stops every other minute to whet, he pares one hair's breadth after another so fine that a dozen have to be cut before the ribbon is perceptibly narrowed. A glance over the rim of his goggles now brings a boy to the 'hibachi', who quickly starts a glow among the three or four bits of charcoal by blowing the flame through a bamboo stick with the bellows given him by nature.

It is this extreme simplicity of method and' paucity of means to do with that makes a piece of fine Japanese work of any kind seem little short of a miracle to a "foreign barbarian." It compels an intimacy with raw materials and a sharpening of the faculties that amount in practice to an added sense. A few minutes of blowing and the strips are all cut, the coals bright red and all in readiness. Taking the bamboo tube from the boy and with the other hand deftly picking up a little platinum dish of the gold shavings with a pair of chop-stick tongs, the operator balances the dish nicely on the coals. Before a degree of heat has been reached sufficient to melt the gold, he carefully picks out one of the hot wires, and laying it on a steel plate he rolls it with a spatula until the angles and kinks have disappeared and the wire itself is as fine and even as a hair from a baby's head and almost as pliable. All are treated in turn, and the materials are now ready for manipulation.

A favorite Japanese treatment of damaskeen, as has been said, is a medallion outlined boldly with a coarse wire, within which a design is delicately wrought in gold, it may be in the space of a square inch, to represent, say, a temple garden or a palace park–both subjects commending themselves for minuteness of detail in foliage, water, boats, lanterns, temple roofs, distant mountains, and clouds with an inevitable flight of birds disappearing into them. The ground is then completely filled with some all-over pattern of chrysanthemums or Paulownia, for instance, executed with almost microscopical delicacy and precision.

The article to be decorated may be a fan-shaped jewel box. A medallion of the same shape will be outlined on the lid in coarse silver wire and filled in to represent a vista of hills with water and pine-tree foliage in the background, while the body of the box may be covered with a running pattern of tufts of pine needles. A Greek key may finish the edge of the lid, and the bottom may be covered with an all-over adaptation of the Greek key–a pattern which the Japanese, however, claim as an independent invention of their own, suggested by the lightning. The two steps already described are quite mechanical,

but to produce a pattern or design requires not only a delicate touch and a knowledge of metals amounting almost to an instinct but the ability at least to copy with the utmost accuracy, if not to work a design out and out in free hand. The cross-hatched surface of iron is such as to make a preliminary outline drawing impracticable. The artisan is an artist to the extent that his eye alone must guide and determine his work. When he has mastered his means of expression, his task is the artist's task to make a sketch. lie makes it on an iron plate in lieu of paper with gold wire tracery in place of ink.

Picking up a wire, he touches it to the iron, guides it along with the chisel to form the line he has in mind–a mountain slope, the sag of a cottage thatch, or the pinion of a bird–cuts it oft at the proper length by a slight pressure of the chisel edge and gives the line a few taps with a spidery hammer, repeating the process till the main features of the design are indicated.

The entire plate is then given a thin coat of lacquer, through which, when dried, the gold work is easily made to appear on being rubbed with a steel polisher. The plate is thus made ready for the next less important details. These are then added and lacquer is again applied. The process may be repeated' until a design has been worked over twenty times. By such a mode of procedure, the workman is not only enabled to keep the proper proportions of space which the infinitude of details might otherwise encroach upon, In it lacquer has been so forced into the pores of the iron as to make it proof against rust,

though lacquer does not at all appear on the finished surface. When the last trace of gold has been inlaid, the piece of work, if a receptacle, as a box, vase, or shrine, rather than a flat surface, as a panel or plaque, is lined with gold by hammering a sheet of the pure metal directly upon the interior surface. The whole is then carefully burnished and the work is complete.

Considered as workmanship, damaskeen has great durability. When one end of a wire has been touched to the iron and given a smart tap or two with the hammer, it is possible to draw a heavy plate freely about on the table by the wire or even to lift it in the air. The wire will break before the end will be detached.

To the general field of decorative art, damaskeen holds a relation somewhat similar to that of the sonnet to poetry. The problem is unlimited embellishment of the "scanty plot of ground" enclosed within the rigid limitations of material and space: and to the solution of this problem anything at all in the works of nature or the arts and imaginations of man may be called upon to contribute a design. As may be expected, the national fancy for a grotesque effect finds expression in damaskeen as in everything else the Japanese artist touches ; but the naturally fine taste of this truly aesthetic people always prevents the perpetration of an offence of any kind.

To illustrate the range of ingenuity shown in the selection of a design, I recall a little tray with a cottage and overhanging plum tree in full bloom in the medallion – a theme as common as it is pretty. The medallion was set in the usual net of filagree work, but in the cramped space of each of the interstices was displayed some implement or utensil of the kitchen or general household economy, as if the cottage had been ransacked to provide the scheme for its own setting. A delicately outlined teapot, a gridiron, a dustpan, a shovel and tongs, and forty other homely things all came to light on a close inspection

of the work.

The most ambitious piece of damaskeen I have ever examined was a large iron plaque, representing a theme in which religion, mythology and drollery were combined in about equal proportions. The tracery in this case poetically stood for the unsubstantial veil that is felt to be between this material world and the realm of spirits. Behind it and striving to break through its meshes were horrid monsters of the darkness, which the iron was cleverly used to typify–dragons or hobgoblins with claws, horns, scales, fins and snouts–madIy careering about a temple window, from which a couple of tonsured Buddhist priests were driving them with bell and rosary back to their own proper domain.

Damaskeen may not be an art, and the patience, skill, and' taste required to damaskeen may not amount to genius; but in that case the old definition is at fault which makes genius an "infinite capacity for taking pains."

Source: The Trader and Canadian Jeweller - August 1920

Trev.

Re: Chinese Export Silver & Far East Trade Information

SOGO

Japan

Member davidross supplied the following information:

Uppermost is a jungin mark, here written in ancient-style characters. The use of archaic style characters would have been a matter of taste, similar to the use of gothic script to suggest tradition.

The lower mark is the trademark / logo of the Sogo Department Store, the retailer of the tray. Sogo was founded in 1830 in Osaka and is still in business today. Wikipedia has a short article about Sogo:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sogo

The tray appears to have no maker's mark, which was not uncommon for Japanese department store silver. Both the subject matter and marks suggest that the tray dates from the first two decades of the twentieth century, so it was probably already a quarter century or more old at the time of its purchase in Nagoya. Sogo's stronghold is the Kansai region, so it makes sense that they tray would have been bought in Nagoya.

Trev.

Japan

Member davidross supplied the following information:

Uppermost is a jungin mark, here written in ancient-style characters. The use of archaic style characters would have been a matter of taste, similar to the use of gothic script to suggest tradition.

The lower mark is the trademark / logo of the Sogo Department Store, the retailer of the tray. Sogo was founded in 1830 in Osaka and is still in business today. Wikipedia has a short article about Sogo:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sogo

The tray appears to have no maker's mark, which was not uncommon for Japanese department store silver. Both the subject matter and marks suggest that the tray dates from the first two decades of the twentieth century, so it was probably already a quarter century or more old at the time of its purchase in Nagoya. Sogo's stronghold is the Kansai region, so it makes sense that they tray would have been bought in Nagoya.

Trev.

Re: Chinese Export Silver & Far East Trade Information

"MR. TIFFANY"

Peking

A Circular from "Tiffany" of Pekin

A few years ago 'Printers' Ink' reported the advertising activities of Mr. Tiffany, who had no connection with the New York firm, but who was a self-educated Chinese jeweler, and reputed to be the leading jeweler of Pekin, China. There has recently come to 'Printers' Ink' a printed circular, dated June 10, 1922, that tells of Mr. Tiffany's death, and that seeks to safeguard the good-will that was created by this advertising Chinese jeweler. This circular, signed by Mrs. Tiffany, reads:

"The public is here by notified that owing to mr. Tiffany was deid on the 1st of June of this year a Successor mr. Peny-yung-fu will take his place as well as who is a student of mr. Tiffany all of the goods which we have been sold are guaranteed, even can he changed with each other and I am here declared of that no more person as such the name Tiffany in China except of mr. Peng yung fu & Chin pao shan i e one of his student & the other of his son."– 'Printers' Ink'.

Source: The Jewelers' Circular - 29th November 1922

Trev.

Peking

A Circular from "Tiffany" of Pekin

A few years ago 'Printers' Ink' reported the advertising activities of Mr. Tiffany, who had no connection with the New York firm, but who was a self-educated Chinese jeweler, and reputed to be the leading jeweler of Pekin, China. There has recently come to 'Printers' Ink' a printed circular, dated June 10, 1922, that tells of Mr. Tiffany's death, and that seeks to safeguard the good-will that was created by this advertising Chinese jeweler. This circular, signed by Mrs. Tiffany, reads:

"The public is here by notified that owing to mr. Tiffany was deid on the 1st of June of this year a Successor mr. Peny-yung-fu will take his place as well as who is a student of mr. Tiffany all of the goods which we have been sold are guaranteed, even can he changed with each other and I am here declared of that no more person as such the name Tiffany in China except of mr. Peng yung fu & Chin pao shan i e one of his student & the other of his son."– 'Printers' Ink'.

Source: The Jewelers' Circular - 29th November 1922

Trev.

Re: Chinese Export Silver & Far East Trade Information

Japanese Art Metal Work

"In the manipulation of metals and amalgams like the shakudo, iron enameled with gold, silver and bronze, the Japanese are past masters. The endless versatility and brilliancy of idea which they display, for instance, in their sword guards, is marvellous. They have a way of combining alloys with pure metals and of producing effects by the inlaying and overlaying of metals–often introducing half a dozen different metals into a space not covering an inch, in order to produce a picture of different colors–far beyond the reach and skill of Western artisans. Braziers, incense holders, water-tanks, flower vases, standing lanterns, memorial tablets and tomb doors gave the bronze workers abundance of opportunity to show their skill in handling metal also in larger dimensions. The big bell of Kyoto, 14 feet high by nine feet two inches in diameter, proves that they were thoroughly initiated into the secrets of bronze casting.

"The casting of a memorial lantern, or column for some temple, was usually a public and outdoor affair attended with festive hilarities. Furnaces, bellows, casting pots, tools and appliances were brought to or prepared at the spot, and the details of the process were watched by holiday crowds. Their methods of bronze casting and their jealously guarded secrets of alloy, niello and metallic work seem to be of Chinese, Persian or Indian origin. At least such is the opinion of experts. The forms and shapes of old temple ornaments and flower vases, in my opinion, point unmistakably to a Persian origin.

"There is a grace and freedom in their work, despite its manifold and minute and delicate details. Nobody can compete with them in representing, for instance, the undulating lines of a lotus leaf. The fidelity in the most minute markings of leaf and flower, even to the motion and color of rain-drops on their cup-shaped surfaces, is amazing as it is inimitable. Their bronze birds, fishes and insects seem to be instinct with life, so true are they to nature. In expressing the attitudes and motions of fish and fowl, and the sportive grace of domestic animals and little forest creatures, they have never been surpassed. Remarkable also is their knowledge of the value of reflected light in relation to metal composition. It endows their work with a rare pictorial quality.

"In the XV. century the Goto and Sojo families excelled in metal works. The XVII. century was the classic age for metal work. The bronzes of this time have a certain severity of form, great vigor in the modelling and a dull black color. In the following century the forms become more graceful in line, and the color effect was heightened by the inlaying and overlaying of metals. This age also produced the greatest workers in cire perdu. The principal artists of this period were Seimin and Taoun, both incomparable in the mastery of their material: Tiyo, Keisai, Jiogioko, Somin, Seifu, Tokusai and Nakoshi. The signature of any of these men on a piece of work guarantees its artistic value.

"Although modern work does not come up to the standard of the old, it is at times very beautiful. The bronzes, set with jewels, which created such a sensation at the Centennial Exposition at Philadelphia, show that the metal workers still possess some originality. These jewel-incrusted bronzes have a story. On the hilt, handle and scabbard of the samurai's swords from two to 20 ornaments were embedded, wrought in metal, with the highest art of the metallurgist. After the issue of an imperial edict in 1868 the use of swords was suddenly abolished and the samurais, impoverished as they were, were practical enough to dispose of their feudal weapons. The market, consequently, was glutted with an amazing stock of sword jewels. By a happy thought these gems of art were applied to bronzes, and the results were these quaint vases and jars, which look like the 'Holy Grails' of some Eastern legend."

Sadakichi Hartmann in 'Japanese Art'.

Source: The Jewelers' Circular - 19th October 1921

Trev.

"In the manipulation of metals and amalgams like the shakudo, iron enameled with gold, silver and bronze, the Japanese are past masters. The endless versatility and brilliancy of idea which they display, for instance, in their sword guards, is marvellous. They have a way of combining alloys with pure metals and of producing effects by the inlaying and overlaying of metals–often introducing half a dozen different metals into a space not covering an inch, in order to produce a picture of different colors–far beyond the reach and skill of Western artisans. Braziers, incense holders, water-tanks, flower vases, standing lanterns, memorial tablets and tomb doors gave the bronze workers abundance of opportunity to show their skill in handling metal also in larger dimensions. The big bell of Kyoto, 14 feet high by nine feet two inches in diameter, proves that they were thoroughly initiated into the secrets of bronze casting.

"The casting of a memorial lantern, or column for some temple, was usually a public and outdoor affair attended with festive hilarities. Furnaces, bellows, casting pots, tools and appliances were brought to or prepared at the spot, and the details of the process were watched by holiday crowds. Their methods of bronze casting and their jealously guarded secrets of alloy, niello and metallic work seem to be of Chinese, Persian or Indian origin. At least such is the opinion of experts. The forms and shapes of old temple ornaments and flower vases, in my opinion, point unmistakably to a Persian origin.

"There is a grace and freedom in their work, despite its manifold and minute and delicate details. Nobody can compete with them in representing, for instance, the undulating lines of a lotus leaf. The fidelity in the most minute markings of leaf and flower, even to the motion and color of rain-drops on their cup-shaped surfaces, is amazing as it is inimitable. Their bronze birds, fishes and insects seem to be instinct with life, so true are they to nature. In expressing the attitudes and motions of fish and fowl, and the sportive grace of domestic animals and little forest creatures, they have never been surpassed. Remarkable also is their knowledge of the value of reflected light in relation to metal composition. It endows their work with a rare pictorial quality.

"In the XV. century the Goto and Sojo families excelled in metal works. The XVII. century was the classic age for metal work. The bronzes of this time have a certain severity of form, great vigor in the modelling and a dull black color. In the following century the forms become more graceful in line, and the color effect was heightened by the inlaying and overlaying of metals. This age also produced the greatest workers in cire perdu. The principal artists of this period were Seimin and Taoun, both incomparable in the mastery of their material: Tiyo, Keisai, Jiogioko, Somin, Seifu, Tokusai and Nakoshi. The signature of any of these men on a piece of work guarantees its artistic value.

"Although modern work does not come up to the standard of the old, it is at times very beautiful. The bronzes, set with jewels, which created such a sensation at the Centennial Exposition at Philadelphia, show that the metal workers still possess some originality. These jewel-incrusted bronzes have a story. On the hilt, handle and scabbard of the samurai's swords from two to 20 ornaments were embedded, wrought in metal, with the highest art of the metallurgist. After the issue of an imperial edict in 1868 the use of swords was suddenly abolished and the samurais, impoverished as they were, were practical enough to dispose of their feudal weapons. The market, consequently, was glutted with an amazing stock of sword jewels. By a happy thought these gems of art were applied to bronzes, and the results were these quaint vases and jars, which look like the 'Holy Grails' of some Eastern legend."

Sadakichi Hartmann in 'Japanese Art'.

Source: The Jewelers' Circular - 19th October 1921

Trev.

Re: Chinese Export Silver & Far East Trade Information

Siamese Clock and Watch Trade

An interesting report on the Siamese clock and watch trade was submitted recently to the Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce by Vice-Consul Carl C. Hansen, Bangkok. His report appeared last week in an issue of the 'Daily Consular and Trade Report', and reads as follows:

"Prior to the Siamese fiscal year 1909-10 the imports of clocks and watches into this country were listed by the Bangkok customs with unclassified goods, and consequently no information was available as to the quantity imported before that period. Subsequent figures, however, show considerable demand for these goods, which are not manufactured in this country.

"According to figures furnished by the Bangkok customs the aggregate value of the imports of clocks, watches and parts thereof amounted to $28,313 gold in the fiscal year 1909-10, $38,025 in 1910-11, $71,089 in 1911-12, $67,397 in 1912-13, $77,117 in 1913-14, $47,829 in 1914-15, $39,053 in 1915-16, $81,976, in 1916-17 and $56,870 in 1917-18. Statistics are not available as to the number, kind, or class of these imports, but for the last five years, however, the totals for the weight of these articles have been given as follows: 53,628 kilos in 1913-14, 30,631 kilos in 1914-15, 20,869 kilos in 1915-16, 30,189 kilos in 1916-17, and 7,377 kilos in 1917-18.

"The comparative declared values of the imports of clocks, watches and parts thereof into Siam from the leading foreign countries for the six fiscal years ended March 31, 1918, in ticals (1 tical equals about 37 gold cents), are shown in the following table:

"There appears to be no special demand for any definite kind of timepiece in this country, the local shops containing a great variety of such articles of every grade and type. However, in the line of watches the wristlet watch seems to be in favor, while of clocks the moderate priced wall and table clocks have the preference.

"The import duty on clocks and watches is 3 per cent ad valorem."

Source: The Jewelers' Circular - 6th August 1919

Trev.

An interesting report on the Siamese clock and watch trade was submitted recently to the Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce by Vice-Consul Carl C. Hansen, Bangkok. His report appeared last week in an issue of the 'Daily Consular and Trade Report', and reads as follows:

"Prior to the Siamese fiscal year 1909-10 the imports of clocks and watches into this country were listed by the Bangkok customs with unclassified goods, and consequently no information was available as to the quantity imported before that period. Subsequent figures, however, show considerable demand for these goods, which are not manufactured in this country.

"According to figures furnished by the Bangkok customs the aggregate value of the imports of clocks, watches and parts thereof amounted to $28,313 gold in the fiscal year 1909-10, $38,025 in 1910-11, $71,089 in 1911-12, $67,397 in 1912-13, $77,117 in 1913-14, $47,829 in 1914-15, $39,053 in 1915-16, $81,976, in 1916-17 and $56,870 in 1917-18. Statistics are not available as to the number, kind, or class of these imports, but for the last five years, however, the totals for the weight of these articles have been given as follows: 53,628 kilos in 1913-14, 30,631 kilos in 1914-15, 20,869 kilos in 1915-16, 30,189 kilos in 1916-17, and 7,377 kilos in 1917-18.

"The comparative declared values of the imports of clocks, watches and parts thereof into Siam from the leading foreign countries for the six fiscal years ended March 31, 1918, in ticals (1 tical equals about 37 gold cents), are shown in the following table:

"There appears to be no special demand for any definite kind of timepiece in this country, the local shops containing a great variety of such articles of every grade and type. However, in the line of watches the wristlet watch seems to be in favor, while of clocks the moderate priced wall and table clocks have the preference.

"The import duty on clocks and watches is 3 per cent ad valorem."

Source: The Jewelers' Circular - 6th August 1919

Trev.

Re: Chinese Export Silver & Far East Trade Information

The Jewelry and Silverware Trade in China

Report by Trade Commissioner Lynn W. Meekins Throws Interesting Sidelights on Types of Jewelry Preferred

The jewelry and silverware market in China is the subject of a report written recently by Trade Commissioner Lynn W. Meekins and sent to the Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce at Washington, D. C. This interesting review which appeared in a current issue of the Consular Report reads as follows:

"Chinese tastes differ radically from American and European preferences in jewelry and silverware. As a result, the market in China for American goods of this class may be said to be limited practically to the foreign colony and to the comparatively few Chinese who have been abroad and have developed a liking for foreign articles. With 10,000 Americans and more than 25,000 Europeans now residing in China (all with a high average purchasing power), there is measurable demand for the products of American jewelry and silverware manufacturers, but the interesting variety of wares produced by Chinese gold and silversmiths naturally commands the market, and it would seem worth while for American manufacturers to investigate the feasibility of duplicating these native types of goods.

"Although frequent reference is made to the low purchasing power of the Chinese, the commercial development of China is gradually increasing the prosperity of the merchant class, and they purchase jewelry when occasion arises. This fact is attested by the elaborate establishments of native jewelers, goldsmiths, and silversmiths in Shanghai, Peking, and other cities, which carry on an extensive business. The custom of sending gifts for Chinese holidays, festivals, weddings, and birthdays is a noteworthy factor in the jewelry and silverware trade.

"Jewelry and silverware of foreign manufacture are sold in China by foreign wholesale and retail dealers and by Chinese and European department stores. As a rule the general import houses do not handle these lines, but manufacturers' agents and commission houses do. The American manufacturer may arrange with an agent or a commission house for representation, or he may sell direct to dealers. Traveling salesmen, working through an agency in China, are the best means of developing business. Keen competition is being experienced from European sources; particularly Great Britain, France, and Germany, and most of the foreign dealers in China carry ample stocks of European jewelry and silverware to the exclusion of American lines.

"The Chinese prefer ornate, heavily embossed jewelry to that of simple design. As the import figures indicate, the call for gold-filled and plated articles is greater than that for solid gold, silver, and platinum wares. These include rings, chains, earrings, bracelets, and hair ornaments.

"Diamonds and pearls are the favorite stones, with jade also figuring prominently in settings. Jade brought from Burma is carved in Canton, Peking, and Soochow. Soapstone, resembling colored marble, is used as a substitute, especially in the form of carved ornaments. Diamond rings have been increasing in popularity of late years. Pearl and jade rings, earrings, necklaces, and hair ornaments have a wide sale, it is reported.

"Chinese rings are clumsy as compared with ours. The stones are very large and the settings extremely crude. Nearly all Chinese women and girls wear hair ornaments of some kind. Ornamental combs are popular, and women of the well-to-do classes usually wear bracelets. Wrist watches are sold in considerable quantities.

"Very little gold and scarcely any silver are produced in China, so these metals must be imported, and the price of native-made articles is affected considerably.

"According to the Chinese maritime customs returns, imports of jewelry, goldware, and silverware into China in 1918 were valued at $52,556; in 1919, $82,428; and in 1920, $134,307. Imports of plated jewelry (gold, silver, nickel, etc.) amounted to $285,262 in 1918, $397,883 in 1919, and $382,259 in 1920.

"The percentage of Chinese who have adopted foreign dress is small, and the market for hat pins, scarf pins, cuff links, shirt studs, collar buttons, and similar articles is restricted to the foreign population. Such novelties as gold and silver pens and pencils, pocketknives, cigarette cases, and vanity cases have not a very extensive sale.

"It should be remembered that Chinese customs do not involve the use of the tableware with which Americans are familiar. On the Chinese Government railways and on coastwise and river steamers the tableware is of low quality–steel knives with bone handles, plated forks, and spoons. The same is true in most of the hotels in China.

"American manufacturers of rings, chains, earrings, bracelets, silver vases, and picture frames might well obtain samples of the kinds most popular in China and determine the practicability of making them in the United States. It is in these native-style articles that most of the business is done.

"Chinese gold and silversmiths turn out for the most part a thin product easily bent and broken. The reason is that pure metal, with little or no alloy, is used. Native craftsmen throughout China make many types of jewelry and silverware. So far as known, however, there are no factories using modern machinery.

Source: The Jewelers' Circular - 23rd August 1922

Trev.

Report by Trade Commissioner Lynn W. Meekins Throws Interesting Sidelights on Types of Jewelry Preferred

The jewelry and silverware market in China is the subject of a report written recently by Trade Commissioner Lynn W. Meekins and sent to the Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce at Washington, D. C. This interesting review which appeared in a current issue of the Consular Report reads as follows:

"Chinese tastes differ radically from American and European preferences in jewelry and silverware. As a result, the market in China for American goods of this class may be said to be limited practically to the foreign colony and to the comparatively few Chinese who have been abroad and have developed a liking for foreign articles. With 10,000 Americans and more than 25,000 Europeans now residing in China (all with a high average purchasing power), there is measurable demand for the products of American jewelry and silverware manufacturers, but the interesting variety of wares produced by Chinese gold and silversmiths naturally commands the market, and it would seem worth while for American manufacturers to investigate the feasibility of duplicating these native types of goods.

"Although frequent reference is made to the low purchasing power of the Chinese, the commercial development of China is gradually increasing the prosperity of the merchant class, and they purchase jewelry when occasion arises. This fact is attested by the elaborate establishments of native jewelers, goldsmiths, and silversmiths in Shanghai, Peking, and other cities, which carry on an extensive business. The custom of sending gifts for Chinese holidays, festivals, weddings, and birthdays is a noteworthy factor in the jewelry and silverware trade.

"Jewelry and silverware of foreign manufacture are sold in China by foreign wholesale and retail dealers and by Chinese and European department stores. As a rule the general import houses do not handle these lines, but manufacturers' agents and commission houses do. The American manufacturer may arrange with an agent or a commission house for representation, or he may sell direct to dealers. Traveling salesmen, working through an agency in China, are the best means of developing business. Keen competition is being experienced from European sources; particularly Great Britain, France, and Germany, and most of the foreign dealers in China carry ample stocks of European jewelry and silverware to the exclusion of American lines.

"The Chinese prefer ornate, heavily embossed jewelry to that of simple design. As the import figures indicate, the call for gold-filled and plated articles is greater than that for solid gold, silver, and platinum wares. These include rings, chains, earrings, bracelets, and hair ornaments.

"Diamonds and pearls are the favorite stones, with jade also figuring prominently in settings. Jade brought from Burma is carved in Canton, Peking, and Soochow. Soapstone, resembling colored marble, is used as a substitute, especially in the form of carved ornaments. Diamond rings have been increasing in popularity of late years. Pearl and jade rings, earrings, necklaces, and hair ornaments have a wide sale, it is reported.

"Chinese rings are clumsy as compared with ours. The stones are very large and the settings extremely crude. Nearly all Chinese women and girls wear hair ornaments of some kind. Ornamental combs are popular, and women of the well-to-do classes usually wear bracelets. Wrist watches are sold in considerable quantities.

"Very little gold and scarcely any silver are produced in China, so these metals must be imported, and the price of native-made articles is affected considerably.

"According to the Chinese maritime customs returns, imports of jewelry, goldware, and silverware into China in 1918 were valued at $52,556; in 1919, $82,428; and in 1920, $134,307. Imports of plated jewelry (gold, silver, nickel, etc.) amounted to $285,262 in 1918, $397,883 in 1919, and $382,259 in 1920.

"The percentage of Chinese who have adopted foreign dress is small, and the market for hat pins, scarf pins, cuff links, shirt studs, collar buttons, and similar articles is restricted to the foreign population. Such novelties as gold and silver pens and pencils, pocketknives, cigarette cases, and vanity cases have not a very extensive sale.

"It should be remembered that Chinese customs do not involve the use of the tableware with which Americans are familiar. On the Chinese Government railways and on coastwise and river steamers the tableware is of low quality–steel knives with bone handles, plated forks, and spoons. The same is true in most of the hotels in China.

"American manufacturers of rings, chains, earrings, bracelets, silver vases, and picture frames might well obtain samples of the kinds most popular in China and determine the practicability of making them in the United States. It is in these native-style articles that most of the business is done.

"Chinese gold and silversmiths turn out for the most part a thin product easily bent and broken. The reason is that pure metal, with little or no alloy, is used. Native craftsmen throughout China make many types of jewelry and silverware. So far as known, however, there are no factories using modern machinery.

Source: The Jewelers' Circular - 23rd August 1922

Trev.

Re: Chinese Export Silver & Far East Trade Information

PYT JEWELLER

45-47-49, Jalan SS2/55, 47300 Petaling Jaya, Malaysia

Originally styled Poh Yik Jeweller, the business merged in 1984 with Thye Loong Goldsmiths and Jewellers Sdn Bhd, to become Poh Yik Thye Jewellers Sdn Bhd.

In 1996 the company restyled their name to PYT Gem Trade Sdn Bhd.

In 2006 the company restyled its name yet again to PYT Jeweller (M) Sdn Bhd.

FABERGE COMES TO MALAYSIA

For the first time, items by world renowned jewellers Faberge are being made available in Malaysia.

The latest Faberge collection was launched at Equatorial Hotel Kuala Lumpur by Youth and Sports Ministry Parliamentary Secretary Shahrizat Abdul Jalil recently.

P.Y.T. Jewellers have been given the privilege of distributing the exquisite treasures.

The jewels were first created in the 18th century by Peter Carl Faberge. They included the famous jewelled Easter Eggs.

Some 70 years later, the Victor Mayer Company in Germany was entrusted to carry on the tradition of Faberge in creating masterpieces for their clientèle, which included royalty and heads of state.

Each masterpiece is marked and stamped for authenticity with the Faberge hallmark and the workmaster's mark "V.M".

On display at the launch were 100 pieces comprising Easter Eggs, tie-clips, cuff-links, lockets, egg-pendants, heart-shaped pendants, ear-clips, and other forms of enamelled jewellery.

Faberge jewellery is hand-made and set with exquisite gems like diamonds, rubies, sapphires and emeralds.

Source: New Straits Times - 24th November 1995

Trev.

45-47-49, Jalan SS2/55, 47300 Petaling Jaya, Malaysia

Originally styled Poh Yik Jeweller, the business merged in 1984 with Thye Loong Goldsmiths and Jewellers Sdn Bhd, to become Poh Yik Thye Jewellers Sdn Bhd.

In 1996 the company restyled their name to PYT Gem Trade Sdn Bhd.

In 2006 the company restyled its name yet again to PYT Jeweller (M) Sdn Bhd.

FABERGE COMES TO MALAYSIA

For the first time, items by world renowned jewellers Faberge are being made available in Malaysia.

The latest Faberge collection was launched at Equatorial Hotel Kuala Lumpur by Youth and Sports Ministry Parliamentary Secretary Shahrizat Abdul Jalil recently.

P.Y.T. Jewellers have been given the privilege of distributing the exquisite treasures.

The jewels were first created in the 18th century by Peter Carl Faberge. They included the famous jewelled Easter Eggs.

Some 70 years later, the Victor Mayer Company in Germany was entrusted to carry on the tradition of Faberge in creating masterpieces for their clientèle, which included royalty and heads of state.

Each masterpiece is marked and stamped for authenticity with the Faberge hallmark and the workmaster's mark "V.M".

On display at the launch were 100 pieces comprising Easter Eggs, tie-clips, cuff-links, lockets, egg-pendants, heart-shaped pendants, ear-clips, and other forms of enamelled jewellery.

Faberge jewellery is hand-made and set with exquisite gems like diamonds, rubies, sapphires and emeralds.

Source: New Straits Times - 24th November 1995

Trev.

Re: Chinese Export Silver & Far East Trade Information

MIKUNI PEARL Co.Ltd.

5, Nichome, Muromachi, Nihon-bashi-Ku, Tokyo

Mikuni Pearl Co.Ltd. - Tokyo - 1920

Trev.

5, Nichome, Muromachi, Nihon-bashi-Ku, Tokyo

Mikuni Pearl Co.Ltd. - Tokyo - 1920

Trev.

Re: Chinese Export Silver & Far East Trade Information

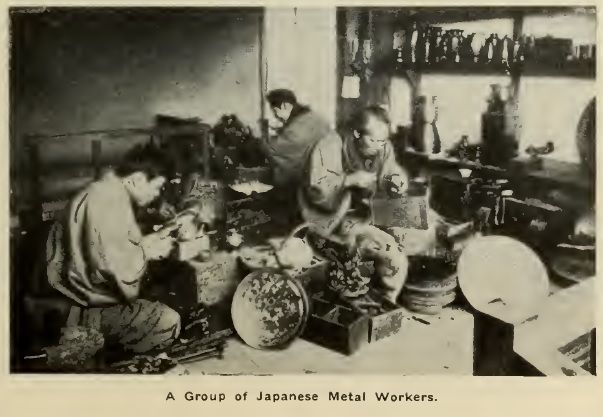

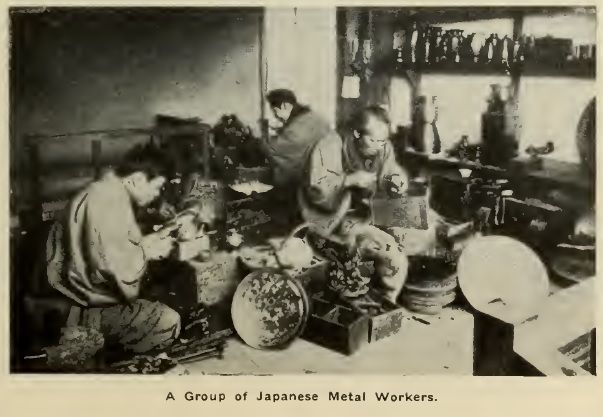

A couple of Japanese metalworking images from 1905:

Trev.

Trev.

Re: Chinese Export Silver & Far East Trade Information

JEWELRY AND SILVERWARE MARKET IN CHINA

Trade correspondent Lyon W. Meekins, July 19

Chinese tastes differ radically from American and European preferences in jewelery and silverware. As a result, the market in China for American goods of this class may be said to be limited practically to the foreign colony and to the comparatively few Chinese who have been abroad and have developed a liking for foreign articles. With 10,000 Americans and more than 25,000 Europeans now residing in China (all with a high average purchasing power), there is measurable demand for the products of American jewelry and silverware manufacturers, but the interesting variety of wares produced by Chinese gold and silver smiths naturally commands the market, and it would seem worth while for American manufacturers to investigate the feasibility of duplicating these native types of goods.

Although frequent reference is made to the low purchasing power of the Chinese, the commercial development of China is gradually increasing the prosperity of the merchant class, and they purchase jewelry when occasion arises. This fact is attested by the elaborate establishments of native jewelers, goldsmiths, and silversmiths in Shanghai, Peking, an other cities, which carry on an extensive business. The custom of sending gifts for Chinese holidays, festivals, weddings, an birthdays is a noteworthy factor in the jewelry and silverware trade.

Sales Methods

Jewelry and silverware of foreign manufacture are sold in China by foreign wholesale and retail dealers and by Chinese and European department stores. As a rule the general import houses do not handle these lines. but manufacturers’ agents and commission houses do. The American manufacturer may arrange with an agent or a commission house for representation, or he may sell direct to dealers. Traveling salesmen, working through an agency in China, are the best means of developing business. Keen competition is being experienced from European sources, particularly Great Britain. France, and Germany, and most of the foreign dealers in China carry ample stocks of European jewelry and silverware to the exclusion of American lines.

Types of Jewelry Preferred by the Chinese

The Chinese prefer ornate, heavily embossed jewelry to that of simple design. As the import figures indicate, the call for gold-filled and plated articles is greater than that for solid gold, silver, and platinum wares. These include rings, chains, earrings, bracelets, and hair ornaments.

Diamonds and pearls are the favorite stones, with jade also figuring promimently in settings. Jade brought from Burma is carved in Canton, Peking, and Soochow. Soapstone, resembling colored marble, is used as a substitute, especially in the form of carved ornaments. Diamond rings have been increasing in popularity of late years. Pearl and jade rings, ear-rings, necklaces, and hair ornaments have a wide sale.

Chinese rings are clumsy as compared with ours. The stones are very large and the settings extremely crude. Nearly all Chinese women and girls wear hair ornaments of some kind. Ornamental combs are popular, and women of the well-to-do classes usually wear bracelets. Wrist watches are sold in considerable quantities.

Very little gold and scarcely any silver are produced in China, so these metals must be imported. and the price of native-made articles is affected considerably.

According to the Chinese maritime customs returns, imports of jewelry, goldware, and silverware into China. in 1918 were valued at $52,556; in 1919, $82,428; and in 1920, $134,307. Imports of plated jewelry (gold, silver, nickel, etc.) amounted to $285,262 in 1918, $397,883 in 1919, and $382,259 in 1920.

The percentage of Chinese who have adopted foreign dress is small, and the market for hat pins, scarf pins, cuff links, shirt studs, collar buttons, and similar articles is restricted to the foreign population. Such novelties as gold and silver pens and pencils, pocketknives, cigarette cases, and vanity cases have not a very extensive sale.

Use of Silver Tableware in China

It should be remembered that Chinese customs do not involve the use of the tableware with which Americans are familiar. On the Chinese Government railways and on coastwise and river steamers the tableware is of low quality–steel knives with bone handles, plated forks, and spoons. The same is true in most of the hotels in China.

Chinese Production of Jewelry and Silverware–Imports

American manufacturers of rings. chains, earrings, bracelets, silver vases, and picture frames might well obtain samples of the kinds most popular in China and determine the practicability of making them in the United States. It is in these native-style articles that most of the business is done.

Chinese gold and silver smiths for the most part turn out a thin product easily bent and broken. The reason is that the pure metal, with little or no alloy, is used. Native craftsmen throughout China make many types of jewelry and silverware. So far as known, however, there are no factories using modern machinery.

Source: Commerce Reports - 7th August 1922

Trev.

Trade correspondent Lyon W. Meekins, July 19

Chinese tastes differ radically from American and European preferences in jewelery and silverware. As a result, the market in China for American goods of this class may be said to be limited practically to the foreign colony and to the comparatively few Chinese who have been abroad and have developed a liking for foreign articles. With 10,000 Americans and more than 25,000 Europeans now residing in China (all with a high average purchasing power), there is measurable demand for the products of American jewelry and silverware manufacturers, but the interesting variety of wares produced by Chinese gold and silver smiths naturally commands the market, and it would seem worth while for American manufacturers to investigate the feasibility of duplicating these native types of goods.

Although frequent reference is made to the low purchasing power of the Chinese, the commercial development of China is gradually increasing the prosperity of the merchant class, and they purchase jewelry when occasion arises. This fact is attested by the elaborate establishments of native jewelers, goldsmiths, and silversmiths in Shanghai, Peking, an other cities, which carry on an extensive business. The custom of sending gifts for Chinese holidays, festivals, weddings, an birthdays is a noteworthy factor in the jewelry and silverware trade.

Sales Methods

Jewelry and silverware of foreign manufacture are sold in China by foreign wholesale and retail dealers and by Chinese and European department stores. As a rule the general import houses do not handle these lines. but manufacturers’ agents and commission houses do. The American manufacturer may arrange with an agent or a commission house for representation, or he may sell direct to dealers. Traveling salesmen, working through an agency in China, are the best means of developing business. Keen competition is being experienced from European sources, particularly Great Britain. France, and Germany, and most of the foreign dealers in China carry ample stocks of European jewelry and silverware to the exclusion of American lines.

Types of Jewelry Preferred by the Chinese